The greatest contribution of mining to society is in the local economy – in terms of broad job creation, new business opportunities and increased disposable income filtering through the population.

The mining industry can be the catalyst for broader economic development

This outweighs the fiscal contribution, in terms of mining taxes and royalties paid to governments.

That’s according to the third edition of Role of mining in national economies, a 2016 report by the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) on Zambia and other mining countries throughout the world.

During the decades-long life cycle of a typical mine, from exploration and construction to production and closure, there is a constant flow of money into the economy from a mining operation running into hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

Employees spend their wages and salaries, which creates demand in the local economy and spurs the creation of new businesses; the mine has a constant need of products and services which attracts suppliers into the area, injecting more money into the local economy; these suppliers have their own procurement needs, and the employees of supplier firms in turn spend their wages, creating yet more demand; and throughout the process, overall disposable incomes increase – even among people who are not connected with the mine at all. This is known in economics as the multiplier effect.

And this does not even take into account the economic boost from mine infrastructure such as roads, powerlines, homes, lighting and water facilities, all of which reduce the cost of doing business and attract skilled people.

“As this ICMM report illustrates, mining plays an important role in the economies of many countries,” says Casper Sonesson, Policy Advisor in Extractive Industries at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), cited in the report.

“A recent World Gold Council study showed that the biggest single element in benefit distribution for communities and government comes from procurement by gold mines, not from taxes and royalties,” says Sonneson. Out of a total of $55 billion annual spending in 2012 by the fifteen Gold Council member companies participating in the study, some $35 billion were payments to other businesses, mostly subcontracting and procurement.

This is not just a feature of gold mining, and applies to the mining of copper and other minerals too. Even in less developed countries like Zambia, although most specialist manufactured goods are imported by the mines, almost 100 percent of their services are locally procured. For example, First Quantum Minerals’ Kansanshi Mine, based in the town of Solwezi in North-Western province, spends more than $100 million every year procuring goods and services with local companies.

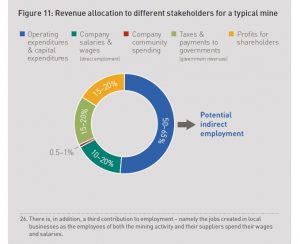

The report identifies who the main beneficiaries are when a typical mine’s minerals are monetised – i.e.: turned into money or revenue. As the accompanying chart shows, the largest beneficiary is employment – in the form of direct employment by the mine (wages and salaries: 10%-20% of the total), as well as indirect employment (arising from the money the mine spends on construction, equipment and running the business: 50%-65% of the total). In contrast, profits paid to shareholders are only 15-20% of the total; tax receipts to governments are also 15-20% of the total.

JOB CREATION

Direct employment

People employed by the mine – for example, truck drivers, mining engineers and contractors.

Indirect employment

People employed by companies that supply goods and services to the mine – for example, building and construction firms, and suppliers or machinery and equipment.

Induced employment

People employed by businesses that have nothing directly to do with the mine, but are in existence wholly or partly because of the mine’s presence – for example, shops, restaurants and hotels.

Developing the subject of employment further, the report argues that official mine employment statistics do not give the full picture. Mining typically contributes only around 1-2 percent of total employment in a country, which is typical of capital-intensive industries. However, when indirect and induced employment is included, “this can jump to 3-15 percent”.

Mining employment in Zambia is listed in the report as 90 000, out of a total employment figure of 5.4 million. However, the multiplier effect referred to above suggests that total employment in the economy as a result of mining could be as high as 800 000. Furthermore, evidence suggests that induced employment – e.g. someone who has opened a shop in a mining region to sell groceries – is “likely to be larger than both direct and indirect employment combined”. Although difficult to measure, because it is the result of many diffused spending decisions by many different people, induced employment “can make a significant contribution to local incomes and create a potential base for diversified development”.

The report analyses the contribution of mining to the economies of 183 countries, with particular importance being attached to the contribution to export earnings, and the value of mineral production as a percentage of GDP. This contribution is quantified in the form of a score: the Mining Contribution Index (MCI). The higher the MCI score for a particular country, the higher the contribution of its mining industry to the economy. The highest possible MCI score is 100.

Of the 183 countries analysed, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) tops the table with an MCI score in 2016 of 96.2. The DRC is followed by Mauritania (95.6); Burkina Faso (94.0) Madagascar (91.7) and Botswana (90.7). Zambia is 28th on the list, with a score of 73.6.

Developed countries with very large mining industries tend to have lower MCI scores, because their economies are diversified and therefore less dependent on mining. For example, Canada is ranked 45th, with an MCI score of 65.7; and the United States is ranked 76th, with an MCI score of 51.8.

“[C]ountries that are the major producers of minerals do not necessarily have a high degree of economic dependence on mineral export activity, whereas an increasing number of smaller but generally poorer countries do show high levels of dependency,” the report says.

A key conclusion of the report is that a country’s mining industry can be the catalyst for broader economic development. “[The] mining and metals sector – if properly managed, regulated and supported – can be a powerful way of helping a lower-income country transition to higher and more sustainable levels of income and long-term development.”