Zambia’s new Government has big plans for the mining sector, with President Hichilema hoping to see the country add some 1.2 million tonnes to annual copper production within a matter of years.

While current operations have potential to increase production by around 400,000 extra tonnes a year – subject to investments in the sector of an estimated $4.3 billion – there’s a finite limit to that which can be achieved through existing mines. Improving Zambia’s mining exploration pipeline in order to find the next generation of mines has therefore never been more urgent. “Quite simply, we’re mining more than we’re exploring,” says Zambia-based geologist Alex Matthews, Country Manager at KoBold Metals, a new type of exploration company that uses statistical modelling and big data aggregation to locate mineral deposits.

Attracting new exploration interest is the key to discovering new mines, which we must do if we are to double, or even treble current levels of production. Conducting a new national survey of Zambia, with the purpose of capturing up-to-date airborne geophysical data of the country, is the missing piece in the puzzle.

What is “airborne geophysical data” and why is it a powerful tool?

Airborne geophysical data is, essentially, a detailed and multi-layered collection of scientific information about the physical properties of a particular part of the planet. The information is gathered via sensors that are attached to aircraft that follow pre-programmed flight lines typically at altitudes of between 40m to 100m above the ground. The data captured from the various sensors is then processed and ‘stitched together’ – in a manner of speaking – with existing data, until a database providing a comprehensive picture of Zambia’s geological architecture gradually forms.

A wide range of data can be captured using airborne platforms – magnetics, radiometrics, electromagnetics, gravity – but generally, it’s the combination of magnetics and radiometrics that help to discriminate between different rock types. “We need to improve our understanding of the country’s prospectivity as a whole,” says Chief Geologist at FQM Zambia, Hugh Carruthers. “We also need to better understand the Copperbelt’s underlying geology in order to find new mines. The only way to do that is with regional coverage, by working from the known to the unknown, and extrapolating what’s there based on magnetics and radiometrics.”

Why do we need new surveys?

Zambia was, in fact, the first country on the continent to obtain airborne geophysical coverage on a national scale, but the dataset acquired in the early 1970’s is extremely low resolution and in analogue format. In recent years the analogue data has been digitised to produce an image of Zambia’s gross geological architecture but, while the data is helpful at this scale, as one zooms in to progressively smaller areas this is no longer the case, and it cannot provide the level of detail that modern exploration teams need. Without this, they are unable to interpret the underlying geology which is key to identifying regional targets for exploration.

Low resolution historical government data (above left) beside modern high resolution magnetic data (above right), showing the same area in Zambia. Both datasets have undergone the same processing without further enhancement. Unlike the old data, the new data could be processed further to improve resolution and yield a wide range of information and approaches to interpretation.

“In order to find the next greenfields projects [in previously unexplored areas or areas where minerals have not yet been discovered] you need airborne geophysical coverage as a first step,” says Mr Carruthers. “If we want to expand Zambia’s exploration footprint, regional geophysics is the only way we’ll have any idea how to identify targets.”

The good old days are behind us

When Zambia’s last national airborne geophysical survey was conducted in the early ‘70’s, the data set was acquired at what’s called a line spacing of 800-1200m. This means that aircraft flew along preset routes (or ‘lines’) that were spaced between 800 and 1200 metres apart. Despite leaving a space of a few hundred metres between flight lines unsurveyed – and conducting these surveys in cumbersome planes that had to fly far higher above the ground than is possible or safe today – Zambia’s data set was state of the art at the time, and the exercise was invaluable for regional mapping and exploration. But when advances in technology and digital data processing arrived in the mid-1980’s, this data became increasingly redundant.

Mineralisation was also relatively easy to locate in the past, because copper deposits at Zambia’s existing mines – with the exception of the Chambishi Southeast ore body – all ‘outcropped’ (meaning the deposits existed within rocks that are exposed at surface level), making them easily visible to the trained eye. “If we are to find the next generation of mines, they more than likely won’t outcrop,” explains Mr Carruthers. “So if you don’t use geophysics you have absolutely no idea what you’re walking over. Geochemistry and geophysics have the potential to see the blind deposits beneath the surface that don’t outcrop, and those are the ones we’ve got to find if we’re going to succeed in boosting copper production.”

“If you don’t use geophysics you have absolutely no idea what you’re walking over. Geochemistry and geophysics have the potential to see the blind deposits beneath the surface.”

A game of risk

Without access to up-to-date airborne geophysical coverage of Zambia, very few investors will be willing to take the enormous financial risk that comes with acquiring the data themselves. With absolutely no guarantee that mineral deposits lie beneath the earth’s surface in quantities that could justify setting up the infrastructure to mine them, for the vast majority of companies, the risk is simply too great.

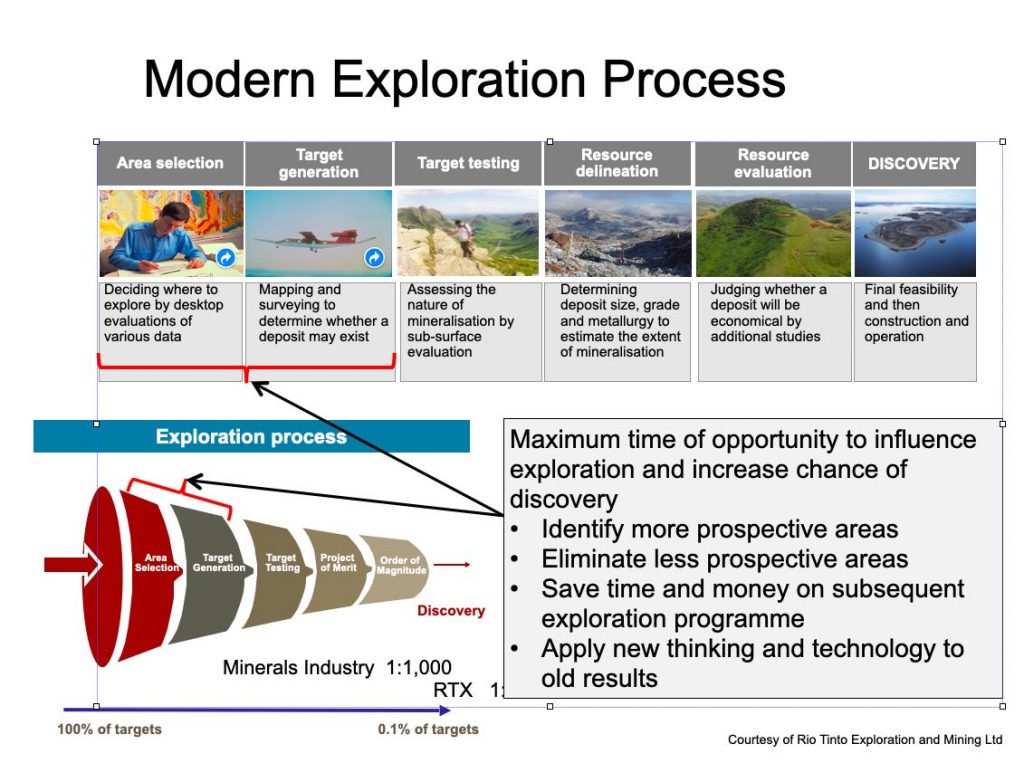

Even when the risk of sunk costs is less of a barrier to investment, Zambia’s lack of current geophysical data adds years onto the process of getting these new mines up and running and, by extension, delays any possible increases in the country’s copper production. This is because, without access to the data they need, explorers have to start at the very beginning. Obtaining high quality geodata sets (using magnetics and radiometrics) can take around a year. Only then can data be stitched together in another year-long process to create geological maps which they can begin interpreting. These maps may or may not help them to identify targets for exploration. This is not to mention the time spent acquiring an exploration license, environmental clearance, and a host of other permissions. Access to high quality geodata sets can reduce lead time by five years, according to Mr Matthews and Mr Carruthers.

But it’s not just about shortening the time it takes for new mines to be built. The fact is, without data to suggest that Zambia has untapped mineral deposits that are worth exploring, companies and investors typically can’t justify the risk of looking in the first place. For starters, how does one pick the area where they apply for an exploration license without any data to guide them? It’s like looking for a needle in haystack.

“The fact is, without data to suggest that Zambia has untapped mineral deposits that are worth exploring, companies and investors typically can’t justify the risk of looking in the first place.”

This is particularly true of minerals other than copper, which has historically been found in the Katanga Basin, home to the rich copper-cobalt deposits that make up the Central African Copperbelt in Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). But finding out where the minerals – including gold, cobalt, nickel, and manganese – that government hopes will diversify the mining sector are located is anyone’s guess.

A national airborne geophysical survey is the first step in creating a map that can be layered with additional details and interpreted, with the ultimate goal of leading you via one of many routes to the proverbial treasure. The technology available to capture data might change over the years, but once you’ve measured the magnetic and radiometric properties of rocks, the raw digital data will not. Collecting it is a once-off exercise that allows this data to be interpreted and reinterpreted for years to come.

“If the data was available off-the-shelf,” explains Mr Carruthers, “an exploration company could simply provide Government with the coordinates of their exploration licence and access the data they need for a nominal fee, before reprocessing and reinterpreting it.”

Charging nominal fees (at most) is a necessary incentive that benefits all parties. Today, it is common for a company to spend the first year or more of their exploration licence acquiring the data they need at a cost of millions of dollars. Providing access to the data that they need would, instead, enable them to be on the ground within months.

There’s competition on our doorstep

Charging no more than nominal fees for access to data like this is also the gold standard of Governments across the region. Botswana, Namibia, and Mozambique have all completed geophysical surveys in recent years, so if Zambia is to remain competitive in the mining world, we need to act fast.

“Think of exploration as critical Research & Development for the mining industry,” says Mr Matthews. “Without exploration, the industry is inherently unsustainable.”

Walking on a proverbial gold (or, copper) mine

If Zambia were to undertake an airborne survey without delay, national geophysical coverage could be realised within three years, with private sector involvement. Working with institutional investors like the World Bank would involve more moving parts which would, inevitably, slow the process to around five years. Setting this exercise in motion now – so that investors can hit the ground running in a few years’ time – is an exciting and viable route to putting Zambia firmly on its path to significantly boosting copper production.

***

In the next instalment of Mining For Zambia’s Exploration series, we explore what steps need to be taken to attract mineral exploration companies, and how we can work towards ensuring that a national survey is funded without delay.

Look out for it on our website or social media platforms, or simply send your address to info@miningforzambia.com to receive an email the minute it’s published. You can also use the ‘mineral exploration’ tag (below) to locate the series any time.

See also: Nurturing Nickel