by Maya Forstater (originally posted on LinkedIn)

On Monday it was widely reported that an $8billion “tax scam” by an unnamed prominent mining company had been discovered. On Tuesday First Quantum Minerals (FQM) gave a short statement: “The Company unequivocally refutes this assessment which does not appear to have any discernible basis of calculation and will continue working with the Zambian Revenue Authority (ZRA) as it normally does, to resolve the issue.” On Wednesday they gave quite a lot more detail on an investor call.

It turns out there was no $8 billion “tax scam” but there are questions about whether $540 million of imports were correctly classified over a five year period, and therefore whether the correct tariff should have been 25%, 15% or 0% on each item (this, if it went beyond ordinary errors to systematic fraud would be “trade misinvoicing” for those following the illicit financial flows definition debates).

The amount in question is $150 million. FQM say these shipments involved 20,000 bills of entry which were signed off by FQM and ZRA over five years. They say that on an initial check they found some errors where items were wrongly classified and either a higher or lower tariff rate was paid, but that this is consistent with an ordinary error, rather than systematic smuggling and underpayment.

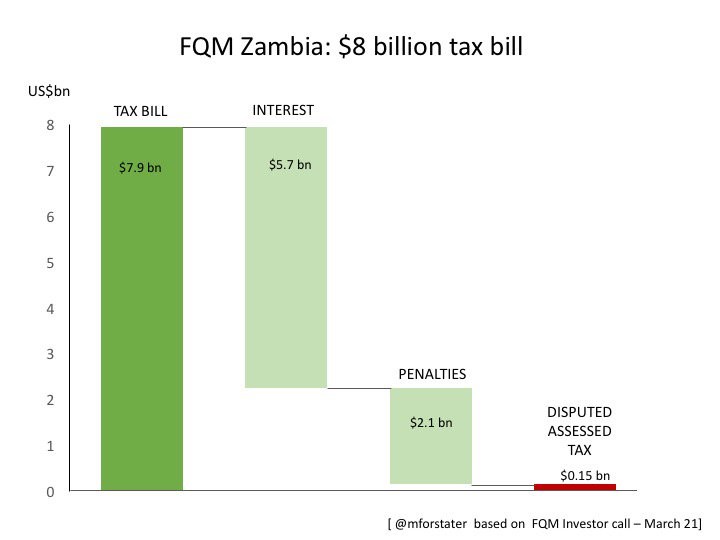

How does $150 million of disputed tax turn into $8 billion? FQM say it was made up of $2.1 billion in penalties and $5.7 billion in interest. (A picture is worth a thousand words here).

The $2.1 billion penalty seems to be based on the fact that smuggling carries a penalty of 300% of the duty paid value of the item (so $540 x 1.25 x 3), with five years of compound interest at a swinging rate presumably adding on $5.7 billion more.

Which seems disproportionate.

In any case smuggling is a criminal act and it would be for the Zambian courts to determine.

What is particularly strange about the case is that it has been put into the public domain like this. If this was intended as a worst-case scenario figure, it will be hard to climb down from it in public (and what most people will have read is that there was an $8 billion tax scam discovered). Such wildly high-stakes negotiating tactics are likely to undermine both investor confidence and taxpayer morale. It will also impact on the willingness of other revenue authorities to share confidential taxpayer information with the ZRA.

If there is tax evasion, or errors by multinational corporations they should pay their taxes and appropriate penalties. But it is not at all clear that there has been systematic evasion in this case. The EU, the World Bank and the Government of Norway have been supporting careful work by the ZRA and the Ministry of Mines to improve the capacity to monitor the quantity, quality and price of minerals exports. More details of what they have found and learned would be valuable, but early accounts are that there are some instances of inaccurate reporting but that it is not systematic across the industry. The idea of an “$8 billion-dollar scam” shifts the disproportionate perceptions of massive misinvoicing to the import channel.While ZRA and FQM will have to sort out their tax dispute, there is a wider issue that the pressure for these trust-destroying tactics will continue as long as there is strong public and political belief that billions of dollars of value from Zambian copper mining are being stolen through trade misinvoicing by major mining companies.

Such high-stakes negotiating tactics are likely to undermine investor confidence and taxpayer morale.

International actors have played a strong role in promoting the belief that Zambia is losing billions to trade misinvoicing and I think they have a responsibility to help to re-examine these assumptions and reset expectations. It may have been honest errors in interpreting gaps and mismatches in trade data, which found their way into international campaigns, films, media stories and official reports, but it is Zambia that is shouldering a disproportionate penalty through the undermining of its political debate and institutions.

Maya Forstater is a visiting fellow at the Center for Global Development and a researcher and advisor on business and sustainable development. Her work focuses on the intersection of public policy, business strategy and sustainability including questions around tax and development, financing for low-carbon investment and multi-sector partnerships and standard setting.

Maya Forstater is a visiting fellow at the Center for Global Development and a researcher and advisor on business and sustainable development. Her work focuses on the intersection of public policy, business strategy and sustainability including questions around tax and development, financing for low-carbon investment and multi-sector partnerships and standard setting.

See also: How mining has made Zambia richer